Abstract

Collision avoidance at sea has always depended on strict adherence to the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs) and the vigilance of bridge teams. But with global shipping growing denser and crews under increasing pressure, new tools are changing what safe navigation looks like. This article explores the foundations of collision avoidance – from COLREG rules and crew responsibilities to the four stages of collision risk – and shows how maritime collision avoidance technology, like Orca AI, is reshaping situational awareness and decision-making to make our oceans and coasts safer.

Introduction

Collisions at sea remain among the most serious risks in global shipping. A single incident can result in loss of life, environmental damage, costly claims and reputational harm. Despite decades of progress in ship design and navigational systems, the fundamentals of avoiding collisions have changed very little: mariners are expected to comply with the globally applicable COLREG rules, maintain a proper lookout and act decisively to mitigate risks when they arise.

But today’s operating environment is more demanding than ever. Traffic density in major sea lanes is increasing, vessels are getting larger and faster (despite the strategy of slow-steaming to conserve fuel), and crews are often stretched thin (both cognitively and in terms of manning). Investigations into recent maritime accidents highlight the same recurring factors – fatigue, delayed reactions or misinterpretation of the rules. In this context, even the best-trained bridge teams face limits to human vigilance.

This is where enhanced maritime situational awareness and maritime collision avoidance technology come into play. By operationalising the principles of the COLREGs – especially the early detection mandate in Rule 7 – AI-powered systems like the Orca AI platform provide crews and fleet managers with a sharper, more reliable picture of developing risks. The result is not a replacement for human judgment but a safer partnership between seafarer and software.

The rules of the sea: COLREGs and collision avoidance

Every vessel, from a small yacht to the largest containership, is bound by the COLREGs, which were first adopted in 1972 and form the backbone of modern navigation. Their purpose is simple: to ensure all mariners follow a common code of conduct so that vessels can anticipate one another’s actions and avoid crashing into each other.

At the heart of the COLREGs are a few critical principles:

- Maintain a proper lookout (Rule 5). Crews must use sight, hearing, Radar, AIS and all available means to remain aware of other vessels and navigational hazards.

- Determine if a risk of collision exists (Rule 7 – see next section). If there is any doubt, mariners must assume that risk is present and act accordingly.

- Give-way vessel obligations (Rule 16). The vessel designated as the “give-way” must alter course or speed early and substantially so that the “stand-on” vessel can clearly see the action being taken.

- Stand-on vessel obligations (Rule 17). The stand-on vessel must initially maintain course and speed but if it becomes clear that the give-way vessel is not acting, it must step in to avoid collision.

These rules apply in specific encounter types: overtaking, crossing or head-on. In each case, COLREGs clearly define which vessel must manoeuvre, removing ambiguity from decision-making. Importantly, verbal agreements over VHF or informal arrangements cannot override COLREG responsibilities – compliance with the rules always takes precedence.

When followed correctly, the COLREGs create predictability at sea. But the challenge lies not in the rules themselves but in their application under pressure. Human fatigue, poor visibility or reliance on incomplete data often lead to delayed or inappropriate responses. That is why situational awareness – and increasingly, decision support from maritime collision avoidance technology – plays such a vital role in ensuring the rules achieve their intended purpose.

Rule 7 explained: risk of collision

Among the 38 COLREG rules, none is more central to safe navigation than Rule 7: Risk of Collision. It defines how mariners must detect and assess danger long before vessels reach a close-quarters situation. Put simply, Rule 7 requires crews to use all available means to determine whether risk exists – and if there is any doubt, to assume it does.

The rule is broken down into four practical requirements:

- Use all means available. This includes visual observation, Radar, AIS and any other tools fitted on board.

- Use Radar properly. Long-range scanning and systematic observation are essential, not just occasional glances at the screen.

- Avoid assumptions. Crews must not act on scanty information, especially from limited Radar returns.

- Recognize danger signs. A steady compass bearing on an approaching vessel usually signals collision risk, even if distance is closing slowly. Risk can also exist when bearings shift, particularly with very large ships, tows or close-range encounters.

In practice, Rule 7 is about continuous situational awareness. For example, a bulk carrier on a steady bearing five NM away may appear harmless to the naked eye but navigational data can reveal a likely crossing point with only minutes to spare. Conversely, a fishing boat altering course erratically might look less threatening but repeated bearing checks could show a dangerous convergence.

Accident investigations repeatedly show that when collisions occur, it is often because Rule 7 was not applied fully. Either the available tools were not used correctly, or assumptions were made too early. This creates what many seafarers call an “illusion of safety” – a dangerous confidence that all is well when in fact risk is building. Read more on the illusion of safety here.

By requiring vigilance and early detection, the rule ensures that vessels have time and sea room to manoeuvre – which is critical in avoiding collisions. This is precisely where technology now strengthens human capability. By fusing Radar, AIS, computer vision and predictive analytics, systems like Orca AI operationalise Rule 7 in real time. Instead of relying on intermittent human checks, the system conducts continuous scanning, calculates Closest Point of Approach (CPA) and Time to CPA (TCPA), and alerts crews to even subtle bearing risks.

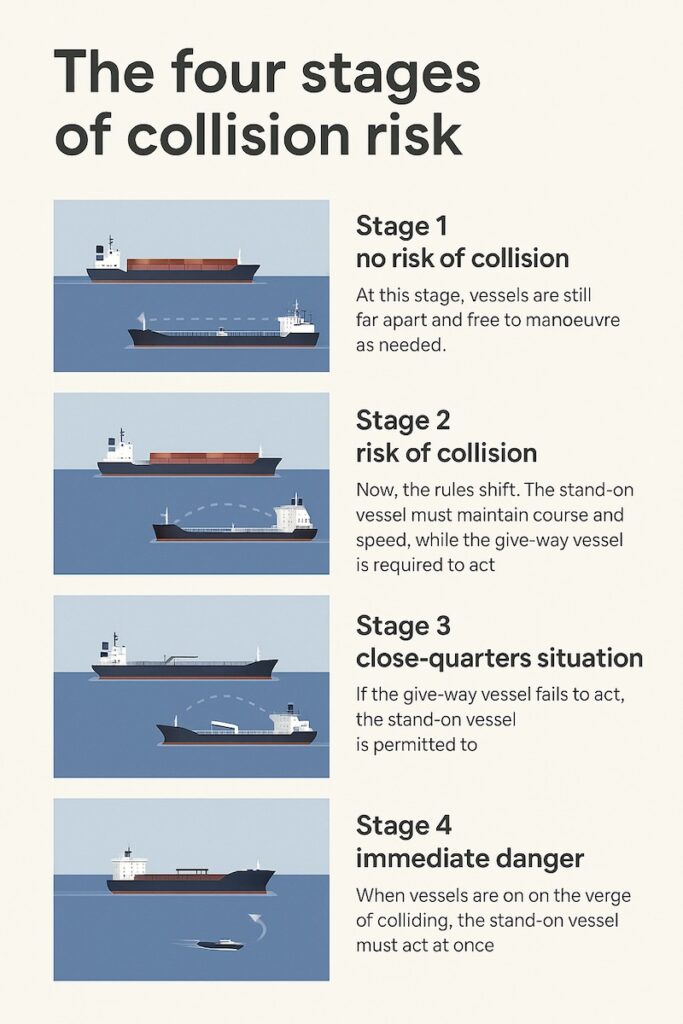

The four stages of collision risk

While Rule 7 tells mariners to detect risk early, the reality on the bridge is that encounters develop over time. Research describes this process in four progressive stages, each with its own responsibilities for the stand-on and give-way vessel, and demanding a different level of response.

Stage 1: no risk of collision

At this stage, vessels are still far apart and free to maneouver as needed. The priority is to avoid ambiguity – any changes of course should be obvious, early and unambiguous.

Rule 7 applied: Crews must remain alert and continually check bearings, even when traffic looks distant.

Enhanced by Orca AI: The system uses Radar, AIS and optical sensors (highly sensitive day and night-thermal cameras) to detect vessels – as well as other targets including non-AIS craft such as fishing vessels – long before the human eye can, logging their movements and projecting future tracks.

Stage 2: risk of collision

Now, the rules shift. The stand-on vessel must maintain course and speed, while the give-way vessel is required to act. The stand-on vessel’s job is to monitor closely and ensure the give-way vessel is manoeuvering properly.

Rule 7 applied: All means – Radar, AIS, visual observation – must be used continuously.

Enhanced by Orca AI: The system calculates DCPA and TCPA in real time, issuing alerts if thresholds are crossed. It also tracks whether the give-way vessel is responding as expected.

Stage 3: close-quarters situation

If the give-way vessel fails to act, the stand-on vessel is permitted to manoeuvre. At this stage, time and sea room are limited, so actions must be bold and decisive.

Rule 7 applied: A change of bearing may no longer mean safety; large vessels or close-range traffic may still pose danger.

Enhanced by Orca AI: By computing the minimum alteration of course needed to avoid breach, the system helps crews select a COLREGs-compliant course change – typically starboard – while maintaining safe separation.

Stage 4: immediate danger

When vessels are on the verge of colliding, the stand-on vessel must act at once, regardless of right of way. This is the last chance to prevent impact.

Rule 7 applied: The situation has escalated beyond theoretical risk; decisive action is now a matter of safety.

Enhanced by Orca AI: Using predictive models and simulations, Orca AI recommends emergency manoeuvres, such as a hard turn in the safest direction, and alerts both crew and shore-based fleet managers through the live dashboard.

The progression through these stages illustrates why early detection is so important. Waiting too long to act – especially in hopes that another vessel will manoeuvre – remains a common cause of incidents. By operationalising Rule 7 across all four stages, Orca AI helps crews avoid collisions at sea with more time, more clarity and less reliance on delayed human judgment.

Crew expectations and bridge roles

The COLREGs define the framework for avoiding collision between vessels but compliance ultimately depends on people. Every member of the bridge team carries specific responsibilities, and lapses in these duties are among the most common causes of maritime accidents.

Officer of the Watch (OOW)

- Primary person responsible for safe navigation.

- Maintains a continuous assessment of traffic, risk of collision and vessel position.

- Monitors Radar, ECDIS, AIS and visual observation to build a complete picture.

- Must log decisions and alert the Master whenever risk escalates.

Master (Captain)

- Holds ultimate authority for the vessel’s safety.

- Must be informed by the OOW when any doubt exists about collision risk.

- Decides on or approves substantial course alterations and liaises with traffic monitoring services ashore or nearby ships if needed.

Helmsman

- Executes helm orders with precision, especially during evasive manoeuvres.

- Communicates immediately if there is any issue with steering response.

Lookout

- Maintains undistracted watch for vessels, objects, lights and sounds.

- Reports sightings promptly to the OOW.

- Should not be given other tasks during critical traffic situations.

Pilot (when embarked)

- Advises on local navigation but the Master remains legally responsible for collision avoidance.

Together, these roles form a safety net. Rule 5 requires a proper lookout “by sight and hearing as well as by all available means”, which means humans must use every tool at their disposal – not just their eyes, but also Radar and AIS – to maintain situational awareness. Yet real-world challenges like fatigue, distraction or over-reliance on electronic aids often undermine this vigilance.

This is why AI-powered decision support is not about replacing seafarers but strengthening them. Systems like Orca AI ensure that continuous monitoring, risk calculations and clear alerts are always active, even when human attention lapses. They act as an ever-present bridge team assistant, allowing officers and masters to make better-informed decisions and act with confidence under pressure. Read more on why AI serves seafarers, not replacing them.

Orca AI as practical implementation

The COLREGs set the rules and bridge teams carry the responsibility, but technology now plays a vital role in ensuring those responsibilities are met consistently. Orca AI translates the intent of Rule 7 – “use all available means” into practical, real-time support for mariners.

How Orca AI maps to COLREG requirements:

- Sensor fusion = “all available means”. Combines Radar, AIS, computer vision and weather inputs to ensure no single point of failure.

- Systematic observation. Tracks bearing and range continuously, updating CPA/TCPA every second.

- Avoiding assumptions. AI models assess risk using rich data streams, reducing reliance on incomplete information.

- Long-range scanning. Automated detection identifies risks far earlier than human observation allows.

Beyond compliance, Orca AI adds new layers of protection. Its risk grading system functions like a Collision Risk Index (CRI), turning raw data into simple risk levels. Its trajectory prediction engine highlights likely near-miss or collision courses before they unfold. And with shore-based FleetView dashboards, operations teams can monitor vessel behaviour in real time or review incidents afterward with synchronized video and data.

The result is not automation for its own sake, but maritime collision avoidance technology designed to strengthen human judgment, uphold COLREGs compliance and reduce the chance of costly incidents. For shipowners, that means safer voyages, fewer claims and higher confidence in their bridge teams. Explore Orca AI’s maritime collision avoidance solutions.

Conclusion: the future of collision avoidance

Avoiding collisions at sea has always been one of the most fundamental duties of seafarers. The COLREGs provide the shared language of the sea, ensuring vessels can anticipate one another’s actions and act in time. Yet as ship traffic grows and crews face tighter operating conditions, the margin for error is shrinking.

The lesson from accident investigations is clear: many collisions could have been prevented if risk had been detected earlier or if crews had acted more decisively. That is why the future of collision avoidance lies not only in training and vigilance, but also in tools that make compliance more reliable.

AI-driven decision support, such as Orca AI, extends human awareness, operationalising Rule 7 across all four stages of collision risk. By fusing multiple data streams, predicting vessel trajectories and alerting crews in real time, the system helps bridge teams act with the clarity and timeliness that COLREGs demand. Just as importantly, shore-based dashboards bring fleet managers into the picture, ensuring lessons are learned and risks are managed beyond the bridge itself.

The result is not a replacement of mariners, but a new partnership: human responsibility reinforced by machine precision. This synergy represents the future of collision avoidance at sea – safer, smarter and more resilient in the face of growing complexity.